I do not have high hopes for such articles that inevitably devote much of the column inches to rehashing the ‘bad boys of punk’ narrative with lurid tales of misogeny, ill-treatment of journalistic unfortunates and Class A drug use. These are stories and anecdotes that compulsorily accompany any article on The Stranglers or past or present members of the band. They add little to our understanding and only elicit the same oft-repeated responses from the interviewees. What remains then for me, the reader, is to scan the piece, with Stranglers’ anorak on, looking for inaccuracies and examples of sloppy journalism.

Did JJ study history? I thought that it was economics…. ‘Harris, now 84, has retired’…. Presumably a mistaken reference to Jet Harris, the now deceased former bass player of The Shadows!

One comment that did stand out for me was Hugh’s assertion that JJ, disdain for ‘Golden Brown’ was such that he did nor appear on the record…. Is this true…. Or just another shot in the ongoing rounds of sniping between the former guitarist and current bass player?

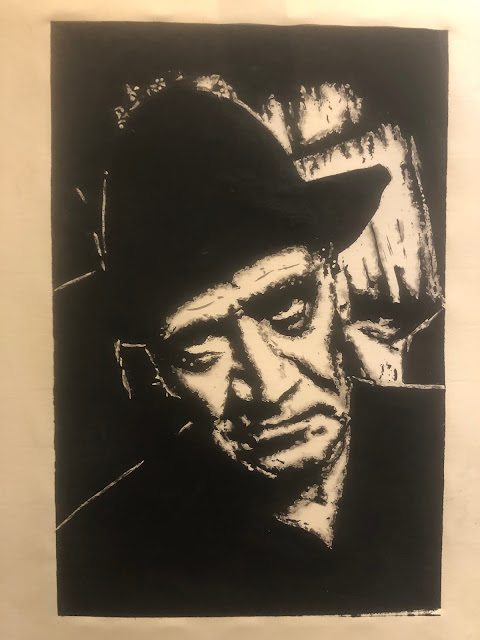

While all of the UK's original punk rock

bands exhibited a dandyish rebel stance, only The Stranglers exuded a genuine

sense of menace.

In their early pictures, the band look

positively thuggish compared to the dyed spiked hair, slogan-smeared T-shirts

and clownish make-up favoured by their contemporaries. “We didn’t dress up or

wear safety pins, we definitely weren’t like the others,” former Stranglers

singer-guitarist Hugh Cornwell tells me.

For a start, they were older. Cornwell

turned 28 in 1977 – the year punk entered the mainstream. Johnny Rotten turned

21.

Behind their scowling image, the four were

professional musicians. As well as being a karate black belt, bassist

Jean-Jacques “JJ” Burnel was a classically-trained guitarist who’d read history

at university.

Keyboardist Dave Greenfield was a piano

tuner with a background in prog-rock. Drummer Jet Black owned a fleet of ice

cream vans and was an accomplished jazz musician. While Cornwell was a

biochemistry graduate whose first band included future Fairport Convention

folk-rocker Richard Thompson.

The Stranglers had spent years playing

London’s hard-to-please pub rock circuit, tightening their skills, before

Peaches became their first of three Top 10 hits in 77.

Hugh tells me, “The necessity of adopting a

pose appealed to our provocative nature. Like Elvis Costello and Blondie, none

of us were really punk. It was an opportunity. Who cares what they called us?

This was our chance to get in through the door.”

The BBC banned Peaches, for “coarse

language and innuendo”, and the band revelled in the notoriety. The song (minus

its lecherous lyrics) famously went on to become the closing theme to the late

Keith Floyd’s TV cooking series…

“Could a group get away with that stuff

now?” ponders Cornwell. “No. Would we be cancelled? We would. But the ones who

complained about Peaches had no sense of humour.

“Nobody has got a sense of humour anymore.

It’s a sad, sad time for the human spirit that people are behaving like this.”

You needed more than a sense of humour to

digest some of The Stranglers’ more antisocial antics, however. Their feuds

with journalists became legendary.

Hugh once tied a French journalist to a

girder of the Eiffel Tower – 200feet above the ground.

JJ kidnapped another hapless hack and

suspended him over a London stage. In Australia, he gaffer-taped a female

journalist to the stage.

“There was also a Portuguese journalist who

we left out in a desert,” Hugh recalls. “But that wasn’t very clever.”

At one stage the notorious Hell’s Angels

adopted the band. “We realised they weren’t there to do us any harm. When we

came offstage, they took us to their clubhouse. They said, ‘Any of these women

you like? They're our girls. Anyone takes your fancy, they’re yours’.”

To refresh the band, the gang served them

amphetamine. “There was a huge knife with a pile of industrial-strength speed,

and you can’t say no…”

This episode was commemorated in their 1978

hit, Nice ‘N’ Sleazy, which they promoted with a now infamous outdoor show in

London’s Battersea Park with a chorus line of onstage strippers.

“The police busted the strippers

afterwards,” Cornwell recalls. “They were trying to take their names and

they’re going, ‘Miss Tubby Hayes’, ‘Tessa Tickell’...all false names and

addresses. It was very funny.”

The joke wore thin after the band agreed to

play a fundraiser for the Angels. “As one of them was escorting us to the stage

we saw two Angels beating the crap out of each other with knives. It all

fizzled out after that.”

Worse was to come for Cornwell however when

in January 1980 he was convicted on drug charges and sentenced to two months in

Pentonville prison.

He “toughed it out, kept my nose clean and

was out in five weeks; you’ve just got to treat it as a new experience that you

can learn from. And I learned that I never want to go to jail again.”

The next two years proved a nadir for The

Stranglers. Album sales held strong, but the hits dried up… until 1982 when

Hugh composed their million-plus-selling single, Golden Brown – number 2 in the

UK, Top Ten in six other countries.

With its dreamy hypnotic allure, Golden

Brown was – unlikely as it sounds – harpsichord-led punk baroque.

London was awash in cheap ‘brown sugar’

heroin at the time and many assumed that the song was about the drug.

Hugh still insists however that “the lyrics

served more than one purpose – there was a girl I was having an affair with who

had beautiful golden-brown skin.”

Burnel never liked the song. “He didn’t

actually play on the record,” says Hugh. “He said, ‘I can’t. This doesn’t turn

me on.’.”

He must have been the only person in the

world that didn’t like it.

Hugh laughs. “Well, he probably likes it

now,” referring to the fact that the record still brings in considerable

royalties.

We meet at a recording studio in west

London, where Cornwell was putting the finishing touches to his first solo

album for three years: Moments of Madness. A less-is-more delight that lets the

music do the talking.

“I’m not trying to knock down any doors

these days,” he says. “I grew up buying Eddie Cochran singles and Cliff Richard

EPs. I’d rather write a great three-minute pop song than a nine-minute epic.”

There are plenty of great three-minute

moments on the album, not least the single, Coming Out of The Wilderness, which

sounds exactly like the sort of catchy one-two-punch that first made The

Stranglers famous.

Hugh left the band in 1990 and has resisted

several lucrative offers to reunite. “Five years after leaving the Stranglers,

there was a seven-figure offer. I said no, and I’ve continued saying no.”

Greenfield died in 2020, aged 71, of

Covid-related causes. Harris, now 84, has retired. And Cornwell is adamant he’s

not interested in teaming up with JJ again.

“I’ve had covert offers. I was told, ‘We

are going to let you re-join the band’. I went, hang on a second, I left. I

wasn’t sacked! Thanks but no thanks.”

He frowns. “They treated me quite

disgracefully after I left. Never wished me luck or anything. It was sad because

we’d spent so much time together.’

Little changed from his Stranglers heyday,

apart from the thinning thatch he still insists on pushing up, Hugh kissed

goodbye to his wild years long ago.

“The drugs are off the table because they

end up destroying your cells. The trouble with cocaine, it sobered you up. So

that if you were blind drunk, you could carry on. Ultimately, your body’s going

to pay for that.

“Dope now is so strong. I mistakenly tried

some a few years ago, and I had to sit down in an armchair for three hours, I

couldn’t move.”

Now 73, he tries hard to stay fit and

healthy. “I eat a lot of fish; I don't eat much red meat. I avoid processed

stuff, sausages.”

Hugh is on a 23-date UK tour, his first

since before Covid. “I remember thinking at the end of 2019 how I could use a

year off,” he says. “But not like that!”

His new show is “a game of two halves – the

first is my solo stuff, the second is ramming those Stranglers songs down their

throats.”

He hates encores and eschewed them for

years. But has grown tired of fans complaining.

“We’ve gone back to that facade of, ‘Right.

We’re going to walk off stage now, and then we’re going to walk back on, and

then we’re going to play…’.

“You can’t please everybody.”

And as he reminds me, the band he personified

in his black-clad punk days never tried to please anybody but themselves. “I

was always my best judge.”

He still is.